Nothing More Than a Story

Of how I didn’t become a psychiatrist

I’ve been following with interest, admiration, and many other sentiments the work Dr. Mary Doherty has been doing on autistic psychiatrists (a recent talk of hers can be watched here). My fascination isn’t just because of my connection with Mary, or because I’m an autistic researcher working in a field that intersects with psychiatry (clinical neuroscience and developmental psychology). It has to do with my personal history—and the fact that becoming a psychiatrist was my plan A. (And as often goes with plans that get assigned a letter, it didn’t come to fruition.)

I studied medicine for one purpose only: to become a psychiatrist. I endured physics, biochemistry, pathology (though I was good at recognising cells under the microscope), and the endless hours spent measuring blood pressure and palpating abdomens, just to finally arrive at the psychiatry department.

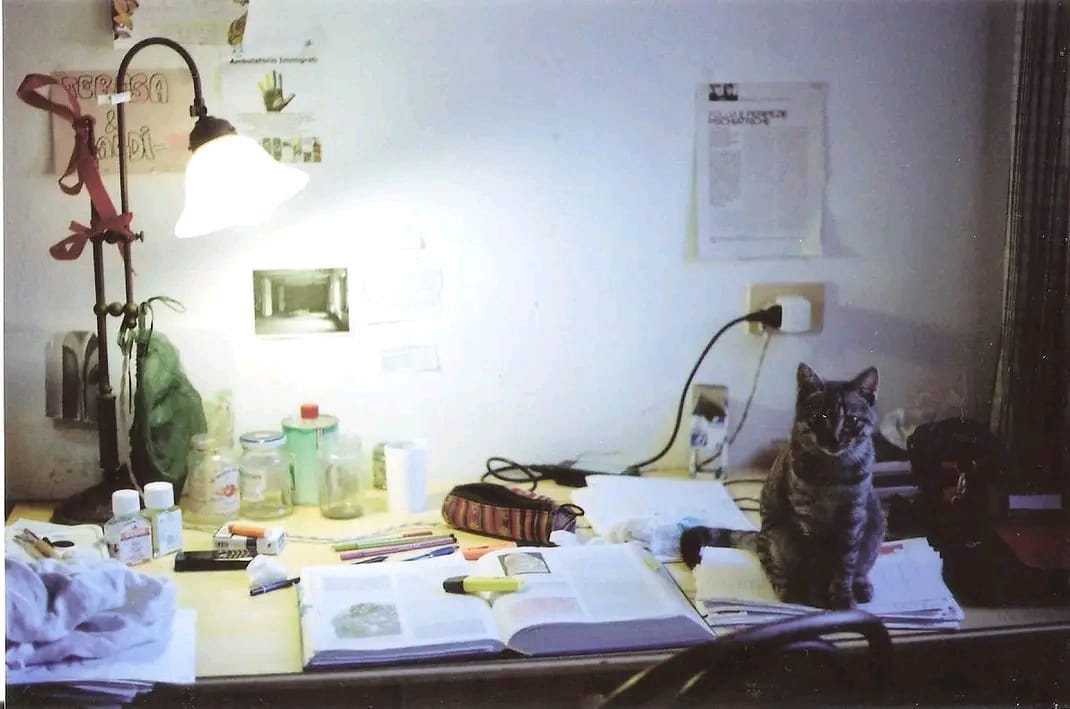

As I worked through tomes of specialisms I didn’t care about, I kept a black-and-white postcard pinned to my desk: a photo of a room in the old mental asylum that sits on the hills just outside my hometown. The room was empty, save for a meagre bed and a skeletal chair. That was the place where I imagined I might end up—and where some of my ancestors did. All I wanted was to go back there, armed with the knowledge and free mind of a psychiatrist.

Well, things didn’t go as planned.

The Ghosts in the Room

I soon discovered I couldn’t stomach the environment. It still felt too close to those ghosts. The quick interviews focused solely on medication, the patients locked in, the overwhelming absence of empathy.

I spent my final-year internship in the infantile neuropsychiatry department, where we saw children and adolescents with a wide range of conditions—from anorexia to epilepsy, speech delay, oppositional defiant disorder. And autism. Many children either under assessment or hospitalised for co-occurring conditions.

The department was a real hospital, nestled on the Tyrrhenian coast, with a massive statue of the Virgin Mary looking down from the entrance. Patient rooms on multiple levels overlooked the main doorway. I remember my first visit on a bright, sunny day. As I walked in, I looked up and saw the silhouettes of patients pacing behind the glass above me.

I felt afraid.

When I left that day, I felt ashamed—and angry. That they had made a place that could scare someone like me, coming in for the first time.

Falling from High

My internship was difficult and raw. Mostly because I couldn’t figure out how to learn from the staff I was supposed to shadow. I was expected to pick up things from the unsaid, to intuit who and when I could ask questions. But I never did.

I dreaded every day of that internship. I fell from very high—from the place where my motivation had carried me through years of longing. For something that, it turned out, didn’t exist.

I also felt I was terrible at assessing autistic children—which, ironically, was the specialism I had imagined for myself, especially after beginning to suspect I might be autistic, too. But none of the children being assessed seemed autistic to me. I failed to pick up the signs my peers and supervisors noticed easily.

Now, of course, I understand why. As Mary’s research has shown, if you’re autistic yourself—and able to navigate the world—you tend to set your idea of “normal” on yourself. That makes it harder to pathologise the same traits in others.

The Unexpected Connections

Something else happened, though. The autistic children who came in for assessment often gravitated straight toward me. I was very shy at the time, and usually stood or sat quietly in the background, trying to make myself invisible. But the children weren’t buying it.

They came straight to me, unprompted.

I remember one girl, maybe 12 years old, who—despite being nearly my height—came over and plopped herself in my lap. I was trying to remain focused on the specialist’s interview, but she just nestled against me and started asking question after question.

And then there was the one I remember best: a chatty five-year-old who came in with her mother for an evaluation session I was shadowing.

Valentina

I still remember her name (I'll call her Valentina), her ash-blond hair, and her minute stature.

As soon as she walked in, she captivated me. Her energy lit up the otherwise dull clinical room. As her mother sat down with the psychiatrist, Valentina wandered over to me, took off her shoes, and began exploring the space—radiating ease, something rare for the constantly-freaked-out medical student that I was.

She landed on a small toy billiards table in the corner. Before I knew it, she was gleefully tossing the balls across the surface, giggling and narrating their every wild movement. Occasionally, she’d pick one up, inspect it, and lick it.

I found myself laughing along with her, throwing balls too. She noticed that the licking threw me off and began teasing me with it. She was charming, playful, completely herself.

And in those moments, I wasn’t just observing—I was playing. I felt like her playmate, part of a game only we understood.

The Report

When the session ended, I sat down with the psychiatrist to review the findings. To my surprise, Valentina had been assessed as severely autistic, with significant communication and cognitive difficulties according to her test scores.

I was stunned.

The vibrant, joyful child I’d just connected with seemed worlds away from the clinical profile I was being presented with. It was a moment of dissonance I couldn’t shake.

Had I missed something? Had I been wrong?

During the session, I had felt calm—proud, even—that she had seemed comfortable with me. But now I felt confused. Was I just naive? Did my emotional response blind me?

Maybe I had equated her playfulness with a lack of difficulty. I had focused on her strengths—the ease of connection, the shared laughter—while missing the repetitive nature of her play, or the sensory seeking behind the licking.

Not Just Valentina

But it wasn’t just about her. It was about me, too—my desperate need to connect, and my growing reluctance to see the world through a diagnostic lens.

What I took away from that moment—from my own shock, and the look on the specialist’s face when they saw it—was that I wasn’t good at this.

And so I jumped ship.

And here I am now, a researcher.

Telling nothing more than a story.

Thank you for reading Silly Musings. Subscribe and share to support my work!